Author: Inta Pujāte, Mag. art.

In the early 20th century, economic boom had made Riga a metropolis and the industrial centre of the Baltic Provinces. The city saw an active cultural life with various associations, several theatres, exhibitions of industry, crafts, agriculture, flowers and art, theatrical and opera performances, concerts and song festivals, visiting circus artists of the widest possible range with the new medium of cinema emerging too. Significant changes happened also in the population; in comparison with the census of 1897, most of Riga’s inhabitants were Latvians (210 000 or 39.65%) in 1913; the next largest ethnic groups were Russians (99 000 or 21.2 %) and Germans (ca. 69 000 or 16.7%).[1]

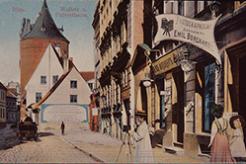

Economic and cultural activities fostered the development of advertising, as seen from many scenes of the early 20th century Riga (ill. 1). Latvian artist Janis Rozentāls ironically commented on this process that influenced European and American cities to an even greater degree: “If Jesus would live in our days, he certainly would place advertisements in newspapers or put posters on view, otherwise he would have to wait a long time for somebody coming to meet him.”[2]

Text was the main carrier of information in Riga’s advertisements of this period; also shifts in the ethnic composition meant that Latvian language appeared increasingly more often alongside Russian and German. Inscriptions were seen on shop signboards (ill. 2) and walls of buildings (ill. 3); text predominated in posters of various kinds (ill. 4), then called in Plakat or plakāts in the Baltic region[3]. Cylindrical advertising columns[4] (ill. 5) patented by the German publisher Ernst Litfaβ (1816–1874) in 1855 appeared on the streets of Riga in the early century. Posters informed about concerts, exhibitions, warned against bad habits and diseases, described the order in trams and trains. Verbal information was often complemented with some image, visualising the key purchase to be made in shops (ill. 6) and the image related to the event advertised by the poster (ill. 7). These advertisements were largely amateurish but the in the 1900s artistically valuable solutions were considered. This process was most evident in the field of culture which saw the earliest manifestations of Art Nouveau forms.

Information in the press and other documents allows us to consider artists involved with poster making, but visual material is much less preserved in comparison with written sources. Because of this the scene is understandably incomplete but it still provides an insight into the traits of Art Nouveau in this field of graphic design.

More information will be available in the virtual exhibition, which will be established till April 2016.

[1] Quoted from: Katram bija sava Rīga. Sast. Volfarte K., Oberlanders E. Rīga: AGB. [b.g.]. 28. lpp.

[2] Dzīves palete: Jaņa Rozentāla sarakste. Sast. Pujāte I., Putniņa-Niedra A. Rīga: Pils, 1997. 128. lpp.

[3] In the early 20th century, the term Plakat or plakāts was used in German and Latvian respectively, meaning both an advertisement with pictures and with text only, the latter more properly called today afiša (Affiche).

[4] Ernst Litfaß [online]. http://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ernst_Litfa%C3%9F (03.05.2014).